Students often refer to Class 8 Maths Notes and Chapter 1 A Square and A Cube Class 8 Notes during last-minute revisions.

Class 8 Maths Chapter 1 Notes A Square and A Cube

Class 8 Maths Notes Chapter 1 – Class 8 A Square and A Cube Notes

→ A number obtained by multiplying a number by itself is called a square number. Squares of natural numbers are called perfect squares.

→ All perfect squares end with 0, 1, 4, 5, 6 or 9. Squares can only have an even number of zeros at the end.

→ Square root is the inverse operation of square. Every perfect square has two integral square roots. The positive square root of a number is denoted by the symbol √.

For example, √9 = 3.

→ A number obtained by multiplying a number by itself three times is called a cube.

For example 1, 8, 27, … ,etc., are cubes.

![]()

→ A number is a perfect square if its prime factors can be split into two identical groups.

→ A number is a perfect cube if its prime factors can be split into three identical groups

→ The symbol \(\sqrt[3]{ }\) denotes cube root.

For example, \(\sqrt[3]{27}\) = 3.

When the exponent or power of a natural number is 2, the number obtained is called a square number or a perfect square.

For example, 32, 52, 82,… are the square numbers or perfect squares.

Square Numbers

Definition of a Square

The square of a number is the product of the number with the number itself, i.e., when a number n is multiplied by n itself, it gives the square of that number and is denoted by n2.

For example: Square of 5 is 52 = 5 × 5 = 25

Square of 8 is 82 = 8 × 8 = 64.

Definition of Square Number

A number that can be represented as a product of another number with itself is called a square number or perfect square.

For example: 16 = 4 × 4 i.e., 42

The number 16 is a perfect square of another number, 4.

Again, 81 = 9 × 9, i.e., 92

∴ The number 81 is a perfect square.

To Check whether a given Natural Number is a Perfect Square or Not

- Step 1: Write the given natural number as a product of primes.

- Step 2: Form pairs of equal prime factors.

- Step 3: If no prime factor is left over after grouping (i.e., forming pairs of equal prime factors), then the given natural number is a perfect square.

- Step 4: If any prime factor or prime factors are left without pairing (or grouping), then the given natural number is not a perfect square.

Example:

Check whether (i) 90, (ii) 81 is a perfect square or not?

(i) Step 1: 90 = 3 × 3 × 2 × 5

Step 2: 3 × 3 × 2 × 5

Step 3&4: 2 × 5 is the leftover prime factor

So 90 is not a perfect square

(ii) 81 = 9 × 9 (No prime factor left)

81 is a perfect square.

Properties of Perfect Squares

Property 1.

A number having 2, 3, 7, or 8 at the unit’s place is never a perfect square, i.e., no square number ends in 2, 3, 7, or 8.

A number ends in 7, the unit place is 7.

Similarly for other digits.

For example: The numbers 72, 83, 14357, 8888, 798328 have 2, 3, 7, 8, 8 in their unit place.

So by property 1, none of them is a perfect square.

Property 2.

The number of zeros at the end of a perfect square is always even.

A number ending in an odd number of zeros is never a perfect square.

For example: 100 = (10)2 is a perfect square and has an even number, here 2 zeros at the end.

250000 = (500)2 is a perfect square and has an even number here 4 zeros at the end.

250 has one zero (i.e., an odd number of zeros) at the end and is not a perfect square.

1000 has three zeros (i.e, an odd number of zeros) at the end and is not a perfect square.

It should be noted that a number ending in an even number of consecutive zeros may or may not be a perfect square.

For example, 500 has 2 (an even number of zeros) at the end is not a perfect square, whereas 900 has 2 (an even number of zeros) at the end and is a perfect square of 30, i.e., 900 = (30)2.

Property 3.

The square of an even number is always even.

For example, 4 is even, and 42 = 16 is also even.

12 is even and 122 = 144 is also even.

Property 4.

The square of an odd number is always odd.

For example, 9 is odd, and 92 = 81 is also odd.

15 is odd and 152 = 225 is also odd.

Property 5.

The unit digit of the square of a natural number is the unit digit of the square of the digit at the unit’s place of the given number.

Examples:

- The unit digit of 392 (= 1521) is the unit digit of the square of the unit digit of 39, i.e., 92 (= 81), i.e., 1.

- The unit digit 1572 (= 24649) is the unit digit of the square of the unit digit of 157, i.e., 72 (= 49), i.e., 9.

Perfect Squares and Odd Numbers

Perfect Squares: A perfect square (or square number) is an integer that can be expressed as the product of an integer multiplied by itself.

In other words, if a number can be written as n2, where ‘n’ is a whole number, it is a perfect square.

Examples: 1 (12), 4 (22), 9 (32), 16 (42), 25 (52).

Relationship with Odd Numbers: A key property of perfect squares is that every perfect square is the sum of consecutive odd numbers starting from 1.

Examples:

- 1 = 1 (1st odd number)

- 4 = 1 + 3 (sum of the first 2 odd numbers)

- 9 = 1 + 3 + 5 (sum of the first 3 odd numbers)

- 16 = 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 (sum of the first 4 odd numbers)

How to check if a number is a perfect square using odd numbers

This relationship provides a method to check if a number is a perfect square.

Process:

- Continuously subtract consecutive odd numbers (starting from 1) from the number we want to check.

- If we eventually reach exactly 0, the number is a perfect square.

- The number of odd numbers we subtracted will be the square root of the number.

- If we get a negative number without reaching 0, it is not a perfect square.

Examples:

- 25 – 1 = 24

- 24 – 3 = 21

- 21 – 5 = 16

- 16 – 7 = 9

- 9 – 9 = 0

Since 0 is reached after subtracting 5 odd numbers, 25 is a perfect square, and its square root is 5.

Triangular Numbers

Numbers whose dot patterns can be arranged as triangles are known as triangular numbers.

The numbers 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21 are triangular numbers. These numbers can be represented by triangles as shown below:

nth triangular number is given by \(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\)

In the above representation, 5th triangular number is \(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}=\frac{5 \times 6}{2}\) = 5 × 3 = 15.

Patterns on Perfect Squares

Pattern 1.

If n is a positive natural number, the sum of the nth and (n + 1)th triangular numbers is (n + 1)2.

Verification:

In the above representation the sum of n = 4th and (n + 1) = 5th triangular number is 10 + 15 = 25 = 52 = (4 + 1)2= (n + 1)2

Pattern 2.

There are 2n non-perfect square numbers between two consecutive square numbers n2 and (n + 1)2.

For example: For n = 4; n2 = 42 = 16 and (n + 1)2 = 52 = 25.

The consecutive natural numbers between n2 = 16 and (n + 1)2 = 25 are 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24.

These are 8 (= 2 × 4 = 2n) natural numbers between n2 and (n + 1)2, which are not square.

Square Roots

The square root of a number a is a number b which when multiplied with itself gives a as the product

i.e. b × b = a or b2 = a

The square root b of a number a is denoted by √a.

Hence, we learn that if b = √a, then a is the square of b, i.e., a = b2.

Example:

- 2 = √4 because 4 = 22

- 3 = √9 because 9 = 32

- 7 = √49 because 49 = 72

Properties of Square Roots

Property 1.

If the unit digit of a natural number is 2, 3, 7, or 8, then no natural number can be its square root.

∴ If a natural number is a perfect square of a natural number and hence has a square root, then the unit digit of the perfect square natural number is 0, 1, 4, 5, 6, or 9.

But converse is not true. 26, 39 are natural numbers ending in 6, 9, but no natural number is their square root.

Property 2.

If a number ends in an odd number of zeros, then it does not have a square root.

250, 2570, 27900 do not have square root.

Property 3.

If a perfect square number is followed by an even number of zeros at the end, it has a square root in which the number of zeros at the end is half the number of zeros in the given perfect square number.

For example:

- √900 = 30

- √60000 = 400

Property 4.

(i) The square root of a perfect square even number is even.

(ii) The square root of a perfect square odd number is odd.

- √144 = 12

- √15376 = 124

- √81 = 9

- √17161 = 131

Property 5.

No integer (or even a rational number) can be square root of a negative integer.

We know that 32 = 3 × 3 = 9 and (-3)2 = (-3) × (-3) = 9.

∴ We can observe that square of an integer whether positive or negative is positive.

Hence, we can say that negative integers are never perfect squares i.e. negative integers have no square roots.

Algorithm to find Square Root of a Perfect Square Natural number by Prime Factorisation Method

- Step 1. Resolve the given number into prime factors by successive division by prime factors.

- Step 2. Make pairs of similar factors, (i.e., factors in each pair are equal). Since the number is a perfect square (given), we will be able to form an exact number of pairs of equal factors.

- Step 3. Take one factor from each pair from pairs of equal factors formed in step 2.

- Step 4. Take the product of these factors taken in step 3 to get the required square root.

Cubic Numbers

Definition of Cube: We have learnt that xn = x × x × x × …….. (n times)

We learnt its particular case, x2 = x × x

and we call it as ‘x raised to the power 2’ or ‘x squared’.

Similarly, x3 = x × x × x,

where x3 is called ‘x raised to the power 3’ or simply ‘x cubed’.

Thus, when a number is multiplied three times by itself, we get the cube of that number.

Examples:

- 13 = 1 × 1 × 1 = 1 that is cube of 1 is 1

- 43 = 4 × 4 × 4 = 64 that is cube of 4 is 64

Caution:

- 53 = 5 + 5 + 5 = 15 is wrong

- 53 = 5 × 5 × 5 = 125 is correct.

Perfect Cube

A natural number n is said to be a perfect cube if it is the cube of some (other) natural number m i.e., m multiplied with itself three times gives n

i.e., n = m × m × m = m3

For example 64 is a perfect cube because there is a natural number 4 such that 64 = 4 × 4 × 4 = 43

Prime factorisation method to check whether a given natural number n is a perfect cube or not.

Step 1: Resolve the given natural number n as a product of prime factors.

Step 2: Group the factors in triples (i.e., three) of equal factors.

Example: Let n = 512

Its prime factor = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2

Step 3: If no single factor or no pair of only two equal factors is left after forming triples of equal factors in step 2, then n is a perfect cube; otherwise not.

Step 4: If n is a perfect cube (checked in step 3), then take one prime factor from each triple of equal factors in step 2 and multiply them to get the natural number m.

Then n is a perfect cube of m i.e., n = m3

So 512 is a perfect cube n = m3 = 223

Properties of Cubes of Natural Numbers

Property 1.

The cube of every even natural number is even.

Property 2.

The cube of every odd natural number is odd.

Property 3.

The sum of the cubes of the first n natural numbers is equal to the square of their sum, that is, 13 + 23 + 33 + ….. + n3 = (1 + 2 + 3 + … + n)2.

For example: 13 + 23 + 33 + 43 + 53 = (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5)2

⇒ 1 + 8 + 27 + 64 + 125 = (15)2 = 15 × 15 = 225

⇒ 225 = 225

Hence result.

Property 4.

(i) Cubes of the numbers ending in digits 1, 4, 5, 6, and 9, respectively, are the numbers ending in the same digit, i.e., ending in 1, 4, 5, 6, and 9, respectively.

For example:

63 = 6 × 6 × 6 = 216

(15)3 = 15 × 15 × 15 = 225 × 15 = 3375

(ii) Cube of a number ending in digit 8 ends in digit 2, and reversely the cube of a number ending in digit 2 ends in digit 8.

For example:

83 = 8 × 8 × 8 = 512

283 = 28 × 28 × 28 = 21952

23 = 2 × 2 × 2 = 8

223 = 22 × 22 × 22 = 10648

(iii) Cube of a number ending in digit 3 ends in digit 7 and cube of a number ending in digit 7 ends in digit 3.

For example:

33 = 3 × 3 × 3 = 27

133 = 13 × 13 × 13 = 2197

73 = 7 × 7 × 7 = 343

173 = 17 × 17 × 17 = 4913

Taxicab Numbers

Taxicab numbers, also known as Hardy-Ramanujan numbers, are the smallest numbers that can be expressed as the sum of two positive cubes in a specific number of distinct ways. The most famous example is 1729, which is the smallest number that can be expressed as the sum of two cubes in two different ways: 13 + 123 and 93 + 103.

Cube Roots

We know that 43 = 4 × 4 × 4 = 64.

We say that 64 is the cube of 4.

In other words, 4 is called cube root of 64.

We know that finding the square root is the inverse operation of squaring.

Similarly, finding the cube root is the inverse operation of finding the cube.

We know that 53 = 5 × 5 × 5 = 125. So, we say that cube root of 125 is 5.

We write \(\sqrt[3]{125}\) = 5

The symbol \(\sqrt[3]{ }\) denotes cube root.

We learn from the above discussion that the cube root of a number is that number which, when cubed, gives the original number.

For example cube root of 8 is 2 because when 2 is cubed, we get 8, and we write it as \(\sqrt[3]{8}\) = 2.

Definition of Cube Root:

A number m is the cube root of n if original number n = m3.

We know that (-4)3 = (-4) × (-4) × (-4) = -64

i.e., (-64) = (-4)3

∴ \(\sqrt[3]{-64}\) = -4

We can learn from it that the cube root of a negative number is negative.

We know that \(\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)^3=\frac{3^3}{4^3}=\frac{3 \times 3 \times 3}{4 \times 4 \times 4}=\frac{27}{64}\)

i.e., \(\frac{27}{64}=\left(\frac{3}{4}\right)^3\)

∴ \(\frac {3}{4}\) is the cube root of \(\frac {27}{64}\)

i.e., \(\sqrt[3]{\frac{27}{64}}=\frac{3}{4}\)

We know that 0.008 = \(\frac{8}{1000}=\frac{2 \times 2 \times 2}{10 \times 10 \times 10}=\frac{2^3}{10^3}\) = \(\left(\frac{2}{10}\right)^3\) = (0.2)3

∴ 0.2 is the cube root of 0.008

i.e., \(\sqrt[3]{0.008}\) = 0.2.

We know that symbol for square root is √. Infact symbol for square root is \(\sqrt[2]{ }\), but square roots are so often used that all people (mathematicians), as a convention, write it only as √.

Successive Differences

It involves finding the differences between consecutive terms and then finding the differences of those differences, and so on, until a pattern (like an arithmetic sequence) emerges.

A Pinch of History

Babylonians (1700 BCE) used lists of squares and cubes for geometry and measurement. Ancient India used terms like varga (square), ghana (cube), and mula (root) in Sanskrit for powers and their origins. Aryabhata and Brahmagupta described squares and roots with geometric meaning. The word “root” (√) in math comes from the Sanskrit mula, meaning the origin or base of something, just like the root of a plant.

Queen Ratnamanjuri had a will written that described her fortune of ratnas (precious stones) and also included a puzzle. Her son Khoisnam and their 99 relatives were invited to the reading of her will. She wanted to leave all of her ratnas to her son, but she knew that if she did so, all their relatives would pester Khoisnam forever. She hoped that she had taught him everything he needed to know about solving puzzles. She left the following note in her will: “I have created a puzzle. If all 100 of you answer it at the same time, you will share the ratnas equally. However, if you are the first one to solve the problem, you will get to keep the entire inheritance to yourself. Good luck.”

The minister took Khoisnam and his 99 relatives to a secret room in the mansion containing 100 lockers.

The minister explained “Each person is assigned a number from 1 to 100.

- Person 1 opens every locker.

- Person 2 toggles every 2nd locker (i.e., closes it if it is open, opens it if it is closed).

- Person 3 toggles every 3rd locker (3rd, 6th, 9th, … and so on).

- Person 4 toggles every 4th locker (4th, 8th, 12th, … and so on).

This continues until all 100 get their turn. In the end, only some lockers remain open. The open lockers reveal the code to the fortune in the safe.

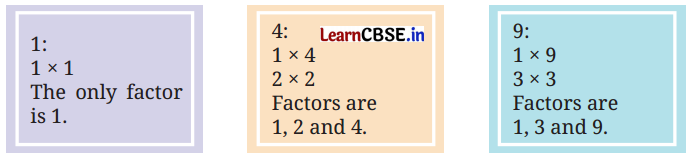

If a locker is toggled an odd number of times, it will be open. Otherwise, it will be closed. The number of times a locker is toggled is the same as the number of factors of the locker number.

For example, for locker #6, Person 1 opens it, Person 2 closes it, Person 3 opens it, and Person 6 closes it. The numbers 1, 2, 3, and 6 are factors of 6. If the number of factors is even, the locker will be toggled by an even number of people, and it will eventually be closed.

Note that each factor of a number has a ‛partner factor’ so that the product of the pair of factors yields the given number. Here, 1 and 6 form a pair of partner factors of 6, and 2 and 3 form another pair.

![]()

Does every number have an even number of factors?

We see in some cases, like 2 × 2, that the numbers in the pair are the same.

Can you use this insight to fid more numbers with an odd number of factors?

For instance, 36 has a factor pair 6 × 6 where both numbers are 6. Does this number have an odd number of factors? If every factor of 36 other than 6 has a different factor as its partner, then we can be sure that 36 has an odd number of factors. Check if this is true. Hence, all the following numbers have an odd number of factors: 1 × 1, 2 × 2, 3 × 3, 4 × 4, …

A number that can be expressed as the product of a number with itself is called a square number, or simply a square. The only numbers that have an odd number of factors are the squares, because they each have one factor which, when multiplied by itself, equals the number. Therefore, every locker whose number is a square will remain open.

Write the locker numbers that remain open.

Khoisnam immediately collects word clues from these 10 lockers and reads, “The passcode consists of the first five locker numbers that were touched exactly twice.”

Which are these five lockers?

The lockers that are toggled twice are the prime numbers, since each prime number has 1 and the number itself as factors. So, the code is 2-3-5-7-11.

Square Numbers Class 8 Notes

If a natural number m can be expressed as n2, where n is also a natural number, then m is a square number or a perfect square. 1, 9, 16, 25, … are perfect squares.

Properties of perfect squares

(a) A number ending in 2, 3, 7 & 8 cannot be a perfect square.

(b) A number ending in odd number of zeros cannot be a perfect square.

1. If n is a perfect square then there must be an integer m such that n = m × m. This integer m is called square root of n. We write m = √n.

2. Every natural number does not have a square root.

3. Finding the square root is just the inverse operation to finding square.

4. Table of square roots up to 400.

5. Properties of square roots:

(a) If the units digit of a number is 2, 3, 7 and 8, it will not have a square root.

(b) If the units digit of a number is 0, 1, 4, 5, 6 or 9, it may have a square root.

(c) A number ending in an odd number of zeros will not have a square root.

(d) A number ending in an even number of zeros may have a square root.

(e) A relationship exists between a perfect square and its square root.

- If units digit of a perfect square is 0, units digit of its square root is 0.

- If units digit of a perfect square is 1, units digit of its square root is 1 or 9.

- If units digit of a perfect square is 4, units digit of its square root is 2 or 8.

- If units digit of a perfect square is 5, units digit of its square root is 5.

- If units digit of a perfect square is 6, units digit of its square root is 4 or 6.

- If units digit of a perfect square is 9, units digit of its square root is 3 or 7.

(f) Square root of an even number if it exists will be even.

(g) Square root of an odd number if it exists will be odd.

6. If m and n are perfect squares then:

(i) \(\sqrt{m \times n}=\sqrt{m} \times \sqrt{n}\)

(ii) \(\sqrt{\frac{m}{n}}=\frac{\sqrt{m}}{\sqrt{n}}\)

Example 1: Which of the following numbers are squares of even or odd number?

(a) 225

(b) 1,296

Solution:

(a) 225 is odd, hence it is a square of an odd number.

(b) 1,296 is even, hence it is a square of an even number.

Example 2:

The following are not perfect squares. Give reasons.

(a) 11,000

(b) 32

(c) 163

(d) 7,777

(e) 10818

Solution:

(a) 11,000 is not a perfect square because it ends in odd number of zeros.

(b) 32 is not a perfect square because it ends in 2.

(c) 163 is not a perfect square because it ends in 3.

(d) 7,777 is not a perfect square because it ends in 7.

(e) 10818 is not a perfect square because it ends in 8.

Example 3:

Find the smallest number by which 9,408 must be divided to make it a perfect square. Find the square root of the number so obtained.

Solution:

Factorising 9,408, we get

9,408 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 7 × 7

Since, 3 has no pair. Hence, we must divide 9,408 by 3 to obtain a perfect square.

Now, 9,408 + 3 = 3,136

3,136 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 7 × 7

So, 3,136 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 7 = 56

Hence, 56 is the square root of the desired number.

Example 4:

Find the smallest square number which is exactly- divisible by 8, 9 and 10. Solution: Let us find least common multiple (LCM) of 8, 9 and 10.

8 = 2 × 2 × 2, 9 = 3 × 3, 10 = 2 × 5

Now, LCM of 8, 9 and 10 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5 = 360

So, 360 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5

Since, 2 and 5 have no pair. Hence, we must multiply 360 by 2 and 5 i.e., 10 to obtain a perfect square.

∴ 360 × 2 × 5 = 360 × 10 = 3,600

3600 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5 × 5

Hence, 3,600 is the required smallest square number.

Why are the numbers 1, 4, 9, 16, … called squares? We know that the number of unit squares in a square (the area of a square) is the product of its sides. The table below gives the areas of squares with different sides.

We use the following notation for squares.

1 × 1 = 12 = 1

2 × 2 = 22 = 4

3 × 3 = 32 = 9

4 × 4 = 42 = 16

5 × 5 = 52 = 25

.

.

.

In general, for any number n, we write n × n = n2, which is read as ‛n squared’.

Can we have a square of sidelength \(\frac{3}{5}\) or 2.5 units?

Yes, there area in square units are \(\left(\frac{3}{5}\right)^2=\left(\frac{3}{5}\right) \times\left(\frac{3}{5}\right)=\left(\frac{9}{25}\right),\) and (2.5)2 = (2.5) × (2.5) = 6.25.

The squares of natural numbers are called perfect squares.

For example, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, … are all perfect squares.

Patterns and Properties of Perfect Squares

Find the squares of the first 30 natural numbers and fill in the table below.

Study the squares in the table above. What are the digits in the units places of these numbers? All these numbers end with 0, 1, 4, 5, 6, or 9. None of them end with 2, 3, 7, or 8.

![]()

The numbers 16 and 36 are both squares with 6 in the units place. However, 26, whose units digit is also 6, is not a square. Therefore, we cannot determine if a number is a square just by looking at the digit in the units place. But the unit digit can tell us when a number is not a square. If a number ends with 2, 3, 7, or 8, then we can say that it is not a square.

The squares, 12, 92, 112, 192, 212, and 292, all have 1 in their units place.

Write the next two squares. Notice that if a number has 1 or 9 in the units place, then its square ends in 1.

Let us consider square numbers ending in 6: 16 = 42, 36 = 62, 196 = 142, 256 = 162, 576 = 242, and 676 = 262.

Perfect Squares and Odd Numbers

Let us explore the differences between consecutive squares. What do you notice?

4 – 1 = 3

9 – 4 = 5

16 – 9 = 7

25 – 16 = 9

See if this pattern continues for the next few square numbers. From this, we observe that adding consecutive odd numbers starting from 1 gives consecutive square numbers, as shown below.

1 = 1

1 + 3 = 4

1 + 3 + 5 = 9

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 = 16

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 = 25

1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11 = 36

Do you remember this pattern from Grade 6?

The picture below explains why each subsequent inverted L gives the next odd number:

We see that the sum of the first n odd numbers is n2. Alternatively, every square is the sum of successive odd numbers starting from 1.

In mathematics, sometimes arguments and reasoning can be presented without any words. Visual proofs can be complete by themselves. Also, we can find out whether a number is a perfect square by successively subtracting odd numbers. Consider the number 25, successively subtract 1, 3, 5, … until you get to or cross over 0,

25 – 1 = 24

24 – 3 = 21

21 – 5 = 16

16 – 7 = 9

9 – 9 = 0

This means 25 = 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 and is thus a perfect square. Since we subtracted the first five odd numbers, 25 = 52.

Using the pattern above, find 362, given that 352 = 1225.

From the question, we know that 1225 is the sum of the first 35 odd numbers. To find 362, we need to add the 36th odd number to 1225.

How do we find the 36th odd number?

The 1st odd number is 1, 2nd odd number is 3, 3rd number is 5, …, 6th odd number is 11, and so on.

What is the nth odd number?

The nth odd number is 2n – 1.

Therefore, the 36th odd number is 71.

By adding 71 to 1225, we get 1296, which is 362.

Consider a number such as 38 that is not a square and subtract consecutive odd numbers starting from 1.

38 – 1 = 37

37 – 3 = 34

34 – 5 = 29

29 – 7 = 22

22 – 9 = 13

13 – 11 = 2

2 – 13 = -11

This shows that 38 cannot be expressed as a sum of consecutive odd numbers starting with 1. Thus, we can say that a natural number is not a perfect square if it cannot be expressed as a sum of successive odd natural numbers starting from 1. We can use this result to find out whether a natural number is a perfect square.

Perfect Squares and Triangular Numbers

Do you remember triangular numbers?

Can you see any relation between triangular numbers and square numbers? Extend the pattern shown and draw the next term.

Square Roots

The area of a square is 49 sq. cm. What is the length of its side?

We know that 7 × 7 = 49, or 72 = 49.

So, the length of the side of a square with an area of 49 sq. cm is 7 cm.

We call 7 the square root of 49.

In general, if y = x2, then x is the square root of y.

What is the square root of 64?

We know that 8 × 8 is 64. So, 8 is the square root of 64.

What about -8 × -8? That is 64 too!

82 = 64, and (-8)2 = 64.

So, the square roots of 64 are +8 and -8.

Every perfect square has two integer square roots. One is positive and the other is negative. The square root of a number is denoted by √.

Thus, √64 = ±8 and √100 = ±10

Note that √82 =±8 and √102 = ±10.

In general, √n2 = ±n

In this chapter, we shall only consider the positive square root.

![]()

Given a number, such as 576 or 327, how do we find out if it is a perfect square? If it is a perfect square, how can we find its square root?

We know that perfect squares end in 1, 4, 9, 6, 5, or an even number of zeros. But, it is not certain that a number that satisfies this condition is a square. We can clearly say that 327 is not a perfect square. However, we cannot be sure that 576 is a perfect square.

1. We can list all the square numbers in sequence and find out whether 576 occurs among them.

We know that 202 = 400, we can find squares of 21, 22, 23, …, and so on until we get 576 or a number greater than 576.

202 = 400

212 = 441

222 = 484

232 = 529

242 = 576

However, this process becomes inefficient for larger numbers.

2. Recall that every square can be expressed as a sum of consecutive odd numbers starting from 1.

Consider √81

81 – 1 = 80

80 – 3 = 77

77 – 5 = 72

72 – 7 = 65

65 – 9 = 56

56 – 11 = 45

45 – 13 = 32

32 – 15 = 17

17 – 17 = 0

From 81, we successively subtracted consecutive odd numbers starting from 1 until we obtained 0 at the 9th step. Therefore √81 = 9.

Can we find the square root of 729 using this method?

Yes, but it will be time-consuming.

3. We know that a perfect square is obtained by multiplying an integer by itself. Will looking at a number’s prime factorisation help in determining whether it is a perfect square?

Yes, if we can divide the prime factors of a number into two equal groups, then the product of the prime factors in either group can combine to form the square root.

Is 324 a perfect square?

324 = 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3.

These can be grouped as

324 = (2 × 3 × 3) × (2 × 3 × 3)

= (2 × 3 × 3)2

= 182

We can also write the prime factors in pairs.

That is, 324 = (2 × 2) × (3 × 3) × (3 × 3), which shows that 324 is a perfect square.

Thus, 324 = (2 × 3 × 3)2 = 182

Therefore, √324 = 18

Is 156 a perfect square?

The prime factorisation of 156 is 2 × 2 × 3 × 13.

We cannot pair up these factors.

Therefore, 156 is not a perfect square.

Find whether 1156 and 2800 are perfect squares using prime factorisation.

We can estimate the square root of larger perfect squares by looking at the closest perfect squares we are familiar with and then narrowing down the interval to search.

For example, to find 1936, we can reason as follows:

- 1936 is between 1600 (402) and 2500 (502), so 40 < √1936 < 50.

- The last digit of 1936 is 6. So, the last digit of the square root must either be 4 or 6. It can be 44 or 46.

- If we calculate 452, we can compare it with 1936 to halve the interval to search from 40 – 50 to either 40 – 45 or 45 – 50.

We can write 452 as (40 + 5) (40 + 5) = 402 + 2 × 40 × 5 + 52 = 1600 + 400 + 25 = 2025. - 2025 > 1936. So, 40 < √1936 < 45

- From the observation in point b, we can guess and then verify that √1936 is 44.

![]()

Consider the following situations:

Aribam and Bijou play a game. One says a number and the other replies with its square root. Aribam starts. He says 25, and Bijou quickly responds with 5. Then Bijou says 81, and Aribam answers 9. The game goes on till Aribam says 250. Bijou is not able to answer because 250 is not a perfect square. Aribam asks Bijou if he can at least provide a number that is close to the square root of 250.

For this, Bijou needs to estimate the square root of 250.

We know that 100 < √250 < 400 and √100 = 10 and √400 = 20.

So, 10 < √250 < 20.

But, we are still not very close to the number whose square is 250.

We know that 152 = 225 and 162 = 256.

Therefore, 15 < √250 < 16.

Since 256 is much closer to 250 than 225, √250 is approximately 16.

We also know it is less than 16.

Here is another problem that requires estimating square roots.

Akhil has a square piece of cloth of area 125 cm2. He wants to know if he can cut out a square handkerchief of side 15 cm. If not, he wants to know the maximum size handkerchief that can be cut out from this piece of cloth with an integer side length.

125 is not a perfect square. The nearest perfect squares are 112 = 121 and 122 = 144.

So the largest square handkerchief with integer side length that can be cut out from this piece of cloth has a side length of 11 cm.

Cubic Numbers Class 8 Notes

1. If n is a non zero integer, then n × n × n written as n3 is called cube of n.

2. Table of cubes up to 20.

3. Properties of cubes

(а) A relationship exists between the units digit of a number and that of its cube.

- If units digit of a number is 1, units digit of its cube is 1.

- If units digit of a number is 2, units digit of its cube is 8.

- If units digit of a number is 3, units digit of its cube is 7.

- If units digit of a number is 4, units digit of its cube is 4.

- If units digit of a number is 5, units digit of its cube is 5.

- If units digit of a number is 6, units digit of its cube is 6.

- If units digit of a number is 7, units digit of its cube is 3.

- If units digit of a number is 8, units digit of its cube is 2.

- If units digit of a number is 9, units digit of its cube is 9.

- If units digit of a number is 0, units digit of its cube is 0.

(b) Cube of an even number is even and that of an odd number is odd.

4. A number n is called a perfect cube or perfect third power if there is an integer k such that n = k × k × k. A perfect cube may be positive or negative.

5. If a number ends in zeros then by observation it is possible to say it may be a perfect cube or not. If the number of zeros in the end is a multiple of three then the number may be a perfect cube. However if the number of zeros in the end is not a multiple of three then the number is certainly not a perfect cube.

6. In the prime factorization of a perfect cube every prime number will occur three times or a multiple of three times.

Taxicab Numbers

Taxicab numbers are the smallest integers that can be expressed as the sum of two positive cubes in a specific number of different ways. The most famous taxicab number is 1729 (also called the Hardy- Ramanujan number). It is the smallest number expressible as the sum of two cubes in two different ways: 13 + 123 = 1729 and 93 + 103 = 1729.

Example 1:

Examine if the following are perfect cubes,

(a) 1,728

(b) 200

Solution:

(а) Factorizing 1,728, we get

1,728 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 3

Clearly, prime factors occur in groups of 3 equal numbers.

Thus, it is a perfect cube.

1,728 = (2 × 2 × 3) × (2 × 2 × 3) × (2 × 2 × 3)

= 12 × 12 × 12 = 123 Hence, 1,728 is a perfect cube of 12.

(б) Factorizing 200, we get

200 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 5 × 5.

Clearly, 5 does not occur in group of three equal numbers.

Thus, it is not a perfect cube.

Example 2. Find the smallest natural number by which 392 must be multiplied so that the product is a perfect cube.

Solution: 392 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 7 × 7

The prime factor 7 does not appear in a group of three. Therefore, 392 is not a perfect cube. To make it a cube, we need one more 7. In that case 392 × 7 – 2 × 2 × 2 × 7 × 7 × 7 = 2744 which is a perfect cube.

Hence, the smallest natural number by which 392 must be multiplied to make a perfect cube is 7.

Example 3: By which smallest natural number should 53240 be divided so that the quotient is a perfect cube?

Solution: 53240 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 11 × 11 × 11 × 5

In the factorisation 5 appears only one time.

If we divide the number by 5, then the prime factorisation of the quotient will not contain 5.

So, 53240 = 5 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 11 × 11 × 11

Hence, the smallest number by which 53240 should be divided to make it a perfect cube is 5.

The perfect cube in that case is 10648.

Cube roots

1. A number m is the cube root of a number n if n = m3.

2. The cube root of a number n is denoted by \(\sqrt[3]{n}\).

Example 4:

Find the cube root of 343.

Solution:

Prime factorisation of 343 is 7 × 7 × 7.

So, \(\sqrt[3]{343}\) = 7

Example 5:

Find the cube root of 8000.

Solution:

Prime factorisation of 8000 is 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 5 × 5 × 5

So, %8000 = 2 × 2 × 5 = 20

You know the word cube from geometry. A cube is a solid figure all of whose sides meet at right angles and are equal. How many cubes of side 1 cm make a cube of side 2 cm?

How many cubes of side 1 cm will make a cube of side 3 cm?

Consider the numbers 1, 8, 27, …

These numbers are called perfect cubes. Can you see why they are named so?

Each of them is obtained by multiplying a number by itself three times.

We note that

1 = 1 × 1 × 1

8 = 2 × 2 × 2

27 = 3 × 3 × 3

Is 9 a cube?

We see that 2 × 2 × 2 = 8 and 3 × 3 × 3 = 27.

This shows that 9 is not a perfect cube.

Nor is any number from 10 to 26.

Can you estimate the number of unit cubes in a cube with an edge length of 4 units?

It has 64 unit cubes! If you notice carefully, each layer of this cube has 4 × 4 unit cubes.

Each square layer has 16 unit cubes (4 × 4), and there are 4 such layers, so the total number of unit cubes is 4 × 4 × 4 = 64.

Since 53 = 5 × 5 × 5 = 125, 125 is a cube.

In general, for any number n, we write the cube n × n × n as n3.

Can a cube end with exactly two zeroes (00)? Explain.

Just as we can take squares of fractions/decimals – \(\left(\frac{4}{6}\right)^2\), (13.08)2, and (-6)2

We can also compute cubes of such numbers \(\left(\frac{4}{6}\right)^3\), (13.08)3, and (-6)3.

\(\left(\frac{4}{6}\right)^3=\left(\frac{4}{6}\right) \times\left(\frac{4}{6}\right) \times\left(\frac{4}{6}\right)=\left(\frac{64}{216}\right)\)

(13.08)3 = 13.08 × 13.08 × 13.08 = 2237.810112

(-6)3 = -6 × -6 × -6 = -216.

![]()

Taxicab Numbers

Once, when Srinivasa Ramanujan was working with G. H. Hardy at the University of Cambridge, Hardy came to visit Ramanujan at a hospital when he was ill. Hardy had ridden in a taxicab numbered 1729, and he remarked that 1729 was ‘rather a dull number,’ adding that he hoped that this was not a bad sign.

Ramanujan immediately replied, “No, Hardy, it is a very interesting number. It is the smallest number that can be expressed as the sum of two cubes in two different ways”.

1729 = 13 + 123 = 93 + 103.

Because of this story, 1729 has since been known as the Hardy-Ramanujan Number. And numbers that can be expressed as the sum of two cubes in two different ways are called taxicab numbers. The next two taxicab numbers after 1729 are 4104 and 13832. Find the two ways in which each of these can be expressed as the sum of two positive cubes.

How did Ramanujan know this? Well, he loved numbers. All through his life, he tinkered with numbers. During Ramanujan’s time in Cambridge, his colleagues often marveled at his ability to see deep patterns in numbers that seemed arbitrary to others. His colleague, John Littlewood, once said, “Every positive integer was one of his [Ramanujan’s] personal friends”.

Perfect Cubes and Consecutive Odd Numbers

Consecutive odd numbers have a role to play with cubes, too. Look at the following pattern:

1 = 1 = 13

3 + 5 = 8 = 23

7 + 9 + 11 = 27 = 33

13 + 15 + 17 + 19 = 64 = 43

21 + 23 + 25 + 27 + 29 = 125 = 53

31 + 33 + 35 + 37 + 39 + 41 = 216 = 63

Later in this series, we get the following set of consecutive numbers:

91 + 93 + 95 + 97 + 99 + 101 + 103 + 105 + 107 + 109.

Cube Roots

We know that 8 = 23.

We call 2 the cube root of 8 and denote this by 2 = \(\sqrt[3]{8}\).

More generally, if y = x3, then x is the cube root of y.

This is denoted by x = \(\sqrt[3]{y}\). So, \(\sqrt[3]{8}=\sqrt[3]{2^3}\) = 2.

Similarly, \(\sqrt[3]{27}=\sqrt[3]{3^3}\) = 3 and \(\sqrt[3]{1000}=\sqrt[3]{10^3}\) = 10.

In general, \(\sqrt[3]{n^3}\) = n.

How do we find out if a number is a cube? Taking inspiration from the case of squares, let us see if we can use prime factorisations.

Let us check if 3375 is a perfect cube.

3375 = 3 × 3 × 3 × 5 × 5 × 5.

Can the factors be split into three identical groups?

For 3375, we can form three groups of (3 × 5).

So, 3375 = (3 × 5) × (3 × 5) × (3 × 5) = (3 × 5)3 = 153.

Another way is to check if the factors can be grouped into triplets:

3375 = (3 × 3 × 3) × (5 × 5 × 5) = 33 × 53.

This means \(\sqrt[3]{3375}\) = 15

![]()

Is 500 a perfect cube?

500 = 2 × 2 × 5 × 5 × 5.

We see that the factors cannot be split into three identical groups. Therefore, 500 is not a perfect cube.

Observe that each prime factor of a number appears three times in the prime factorisation of its cube.

Successive Differences

We know that the differences between consecutive perfect squares give the sequence of odd numbers. Observe the figure below, where the differences are computed successively for perfect squares. After two levels, all the differences are the same.

Compute successive differences over levels for perfect cubes until all the differences at a level are the same. What do you notice?

A Pinch of History Class 8 Notes

The first known list of perfect squares and perfect cubes was compiled by the Babylonians as far back as 1700 BCE. These lists, found on clay tablets, were used to quickly find square roots and cube roots in problems involving land measurement, architectural design, and other areas where geometric calculations were necessary.

In ancient Sanskrit works, the term varga was used both for the square figure or its area, as well as the square power, and the term ghana was used both for the solid cube as well as the product of a number with itself three times. The fourth power was called varga-varga. These terms were used in India at least from the third century BCE.

Aryabhata (499 CE) States

“A square figure of four equal sides and the number representing its area are called varga. The product of two equal quantities is also called varga.” Thus, the term varga for square power has its origin in the graphical representation of a square figure.

Why is the word ‘root’ (the root of a plant) used for the mathematical operation √ (square root, cube root, etc.)?

It is because, in ancient India, the Sanskrit word mula, meaning root of a plant, basis, cause, origin, etc., was used for the mathematical operations of taking roots.

![]()

In Sanskrit, varga-mula (the basis, cause, origin of the square) was used for the square root, and ghana-mula was used for the cube root. This use of mula for the mathematical concept of root was subsequently emulated in Arabic and Latin through their corresponding words for the root of a plant – jidhr and radix, respectively. The term mula for root has been used in India at least from the first century BCE. Another term used was pada (foot, basis, cause, origin). Brahmagupta (628 CE) explains, ‘The pada (root) of a krti (square) is that of which it is a square.’

The post A Square and A Cube Class 8 Notes Maths Chapter 1 appeared first on Learn CBSE.

from Learn CBSE https://ift.tt/lUiJYMb

via IFTTT

No comments:

Post a Comment